After doing extensive archival research on Carleton’s Women’s League Cabin for an archaeology class last term, I would say I’m pretty familiar with the Carleton archives. Still, the research for today’s assignment gave me somewhat of a different perspective on how the archives’ digital collections can be used.

For this assignment, I was gathering images of a building on Carleton’s campus that I will eventually 3d model. I chose Nourse, a dorm I lived in last year whose history intrigues me: once a dorm exclusively for women, it still includes the only all-female floor on campus, as well as the Nourse Little Theater, the history of which I know little about. In 2017 it will reach the hundredth anniversary of its completion. This is one reason why researching Nourse was so different from researching the Women’s League Cabin. While the Cabin served a niche purpose, was located far from campus, and thrived for only a few decades, Nourse has held a prominent place on campus for a century. Because of this, researching the Cabin entailed scouring several archival databases and forms of media but resulted in a much smaller pool of findings, while typing “Nourse” into just the photograph database gave me a wealth of images.

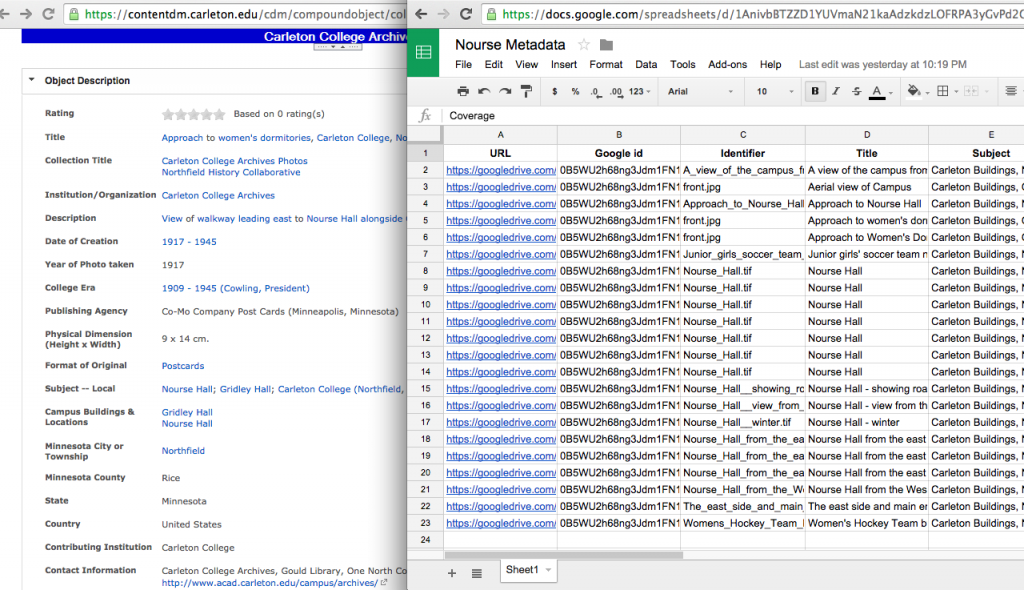

Here is where I encountered the second main difference in the research process. When organizing the data I found on the Women’s League Cabin, I informally scribbled down information on the files in a semi-systematic way I invented. Last week, when we discussed metadata–the data about the data you find or produce for a project–I realized what I had been doing on that project was my own form of metadata. Documenting metadata is an important process for organizing and categorizing files, recording information for future reference, and creating data for any projects building on the original one. But the process is tedious. Entering seventeen pieces of information for dozens of image became incredibly frustrating, especially when I was finding image after image called “Nourse Hall”, all of which featured practically the same shot of the building with slightly different weather or angles. But I know that when the time comes to create a model of Nourse, I’ll be grateful to Harvey E. Stork for taking so many pictures.

This post caught my because I currently live in Nourse. It’s interesting to see how these buildings have either changed or stayed the same over the years. I like how you compared this instance of using the archives to your past experience in your archaeology class. This showed how each attempt can differ depending on the project and person. I do agree the process is tedious, and I definitely echo your statement about Harvey E. Stork!

I really enjoyed reading your post, particularly about your personal reasons for choosing Nourse. It immediately piqued my curiosity: now I want to know all about Nourse, and look forward to learning about it as you do! Also, thanks for mentioning Stork: although my photos had almost no metadata, their file names attribute them to Stork, so now I can add more information to my metadata! Hooray for digital cooperation!

I find your article to be very detailed. Apart from carefully describing your experience with metadata, you also included a screenshot of your computer screen during the process. This makes your blog post easy to follow even for someone outside of our class.

Your post was extremely detailed and super interesting to read! I appreciate the time and effort in all your explanations – I’m sure this would be helpful for someone who wanted to understand the basics of processing metadata.