For the next two weeks we will be exploring the spatial humanities — a vibrant and increasingly popular area of digital humanities research. Humanities scholarship is currently undergoing a “spatial turn” akin to the quantitative, linguistic and cultural “turns” of previous decades, and many are arguing that the widespread adoption of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology and user-friendly neogeography tools are fundamentally reshaping the practice of history and other disciplines. Yet while these powerful computer tools are certainly new, the mode of thinking “spatially” is not unprecedented, and may in fact be seen as a move away from the universalizing tendencies of modern western scholarship towards more traditional understandings of the lived experience of place, emphasizing the importance of the local context.

In practice, much of this scholarship involves creating maps — an act that is not without controversy. Maps are conventional representations of space that come laden with the embedded cultural worldviews of their makers. Maps are also highly simplified documents that often paper over contested or fuzzy boundaries with firm lines; it is hard to express ambiguity with maps, but it is very easy to lie with them.

The familiarity of widespread tools like Google Maps and Google Earth might fool us into thinking these are unproblematic representations of space, but it must be remembered that all maps contain embedded assumptions and cannot be taken at face value. Maps produced in the course of humanities scholarship are not just illustrations but arguments, and they must be read with the same level of critical analysis that you would apply to articles or monographs.

(For more concrete suggestions along these lines, see Humanizing Maps: An Interview with Johanna Drucker.)

Example 1

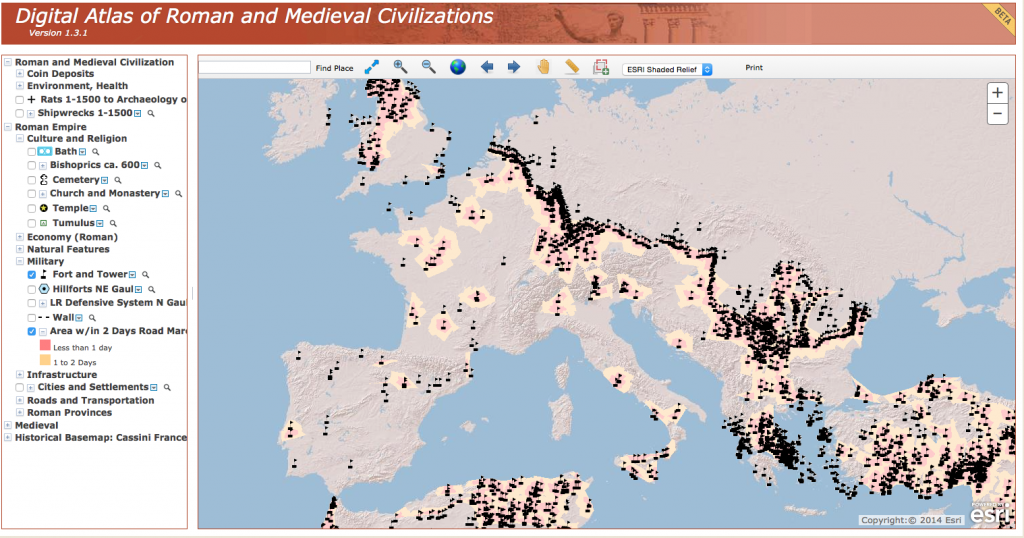

One area of historical research that saw an early adoption of GIS is economic land use. A good example is Michael McCormick’s book on the Origins of the European Economy, which layered many different types of evidence against each other in a GIS to argue for a much earlier origin to Europe’s medieval economy than had been accepted previously. McCormick has since made his database publicly available and continues to add to it with collaborators at Harvard, as the Digital Atlas of Roman and Medieval Civilization.

The DARMC provides a rich resource and a good introduction to the potential of GIS to reveal patterns and connections through the spatial layering of disparate datasets. It also offers a good orientation to the basic layout of most GIS systems, with a map view window on the right and a list of layers on the left that can be turned on and off.

- Explore the DARMC.

- What layers have been included?

- What patterns show up when you juxtapose cultural, environmental and economic data in this way?

- What connections do you see?

- Also take the opportunity to explore the measurement tools at the top of the window to interrogate the spatial attributes of the data.

Example 2

The quantitative data compiled in projects like the DARMC can help address many historical problems, but they don’t necessarily answer more qualitative research questions concerned with the lived experience of the past. For this objective, we must move beyond birds-eye-view 2D maps of spatial distributions and attempt to visualize particular places at particular moments in time. Such “geovisualization,” the digital reconstruction of past landscapes, is another booming area of scholarship that allows us to virtually experience a place as it might have been, and also has the potential to answer important scholarly questions.

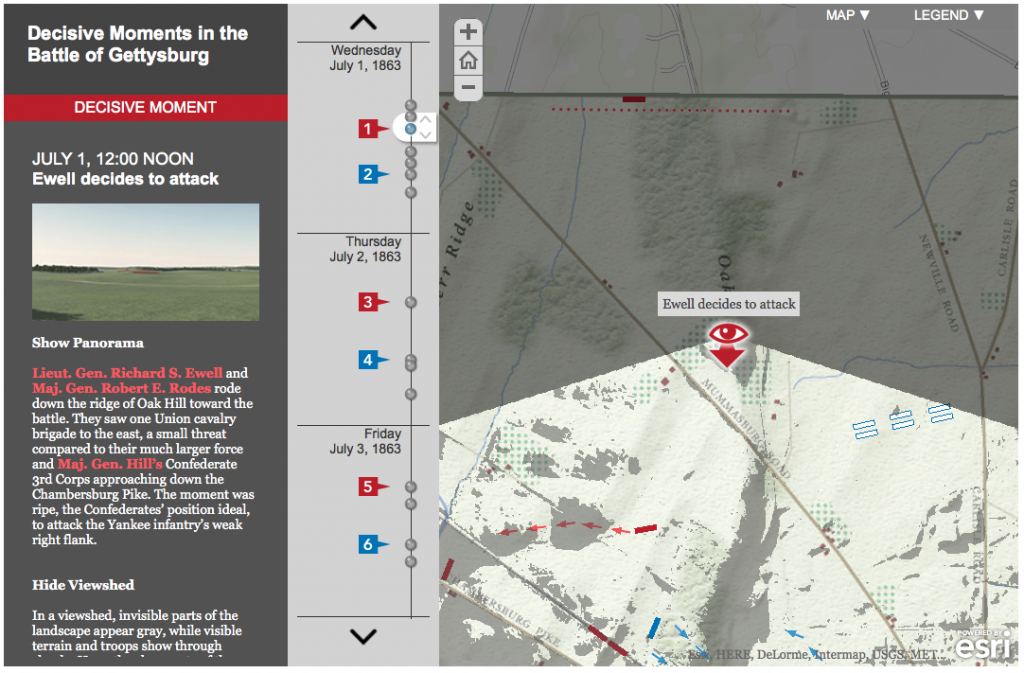

Anne Kelly Knowles’ digital reconstruction of the Battle of Gettysburg is an excellent example of this potential that uses a combination of digitized information from historical maps, documentary accounts and environmental data on the physical geography of the battlefield to answer the question of what the generals could see during the battle and how those sightlines influenced their decision making.

Anne Kelly Knowles’ digital reconstruction of the Battle of Gettysburg is an excellent example of this potential that uses a combination of digitized information from historical maps, documentary accounts and environmental data on the physical geography of the battlefield to answer the question of what the generals could see during the battle and how those sightlines influenced their decision making.

- Read the brief introductory article at Smithsonian magazine and then explore the “story map” in detail.

- How does the map combine geographic and temporal information?

- Does it effectively give you a sense of the experience of being on the battlefield?

- What does this reconstruction offer that more traditional publications could not?

- What could be improved in the representation?

Group Exercise: The Varieties of Maps

(Exercise borrowed from Lincoln Mullen)

The next step is to become familiar with as wide a variety of maps as possible, including digital maps and analog, maps that have been made by scholars and maps that have not. Below is a list of online mapping projects.

In a group, pick three projects from the list to explore and compare. Your aim is to gain familiarity with projects involving maps and mapmaking, both by scholars and on the web generally.

- American Migrations to 1880

- Atlantic Networks Project

- Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States

- Counties Blue and Red, Moving Right and Left

- David Rumsey Map Collection

- Digital Atlas of Roman and Medieval Civilizations

- Digital Harlem

- Digital Harrisburg

- Flowing Data: Coffee, Pizza, Burgers

- Geography of the Post

- Going to the Show

- Hestia: Home for Geospatial Analysis of Herodotus’s Histories

- Hidden Florence

- Histories of the National Mall

- History Pin

- Holocaust Geographies Collective

- How Your Hometown Affects Your Chances of Marriage

- Hypercities

- Locating London’s Past

- A Map of Baseball Nation, Baseball’s Second-Place Favorites: Go, Mets

- Mapping the Republic of Letters

- Mapping the State of the Union

- Mapping Texts

- Map of Early Modern London

- Mapping Gothic France

- Mapping the Medieval Townscape

- Mapping Poverty in America

- Midterm Elections

- Murder Map

- NYPL Map Warper

- Orbis

- PhilaPlace

- Pelagoios

- Pleiades

- Stop and Frisk is All But Gone from New York

- Railroads and the Making of Modern America

- Redlining Richmond

- Ben Schmidt, Mapping ship logs

- Spread of U.S. Slavery, 1790–1860

- Stanford Spatial History Project

- Travelers in the Middle East Archive

- Visualizing Emancipation

As you look through these projects, consider the following questions or prompts.

- Create a taxonomy of maps. What categories do these maps fit into? You might consider the purposes of the maps, their audience, their interfaces, among other axes of comparison.

- What is the grammar of mapping? In other words, what are the typical symbols that mapmakers use, and how are they can they be put in relation to one another?

- Which maps stood out to you as especially good or clear? Why?

- Which maps were the worst? What made them bad?

- How do scholarly maps differ from non-scholarly maps?

- What kind of data is amenable to mapping? What kinds of topics

- What accompanies maps? Who controls their interpretation? What is their role in making an argument?

- How do recent web maps compare to maps made online in the past few years? How can maps be made sustainable?

- Which of these maps are in your discipline? Which maps might be helpful models for your discipline?

Exercise (Georeferencing)

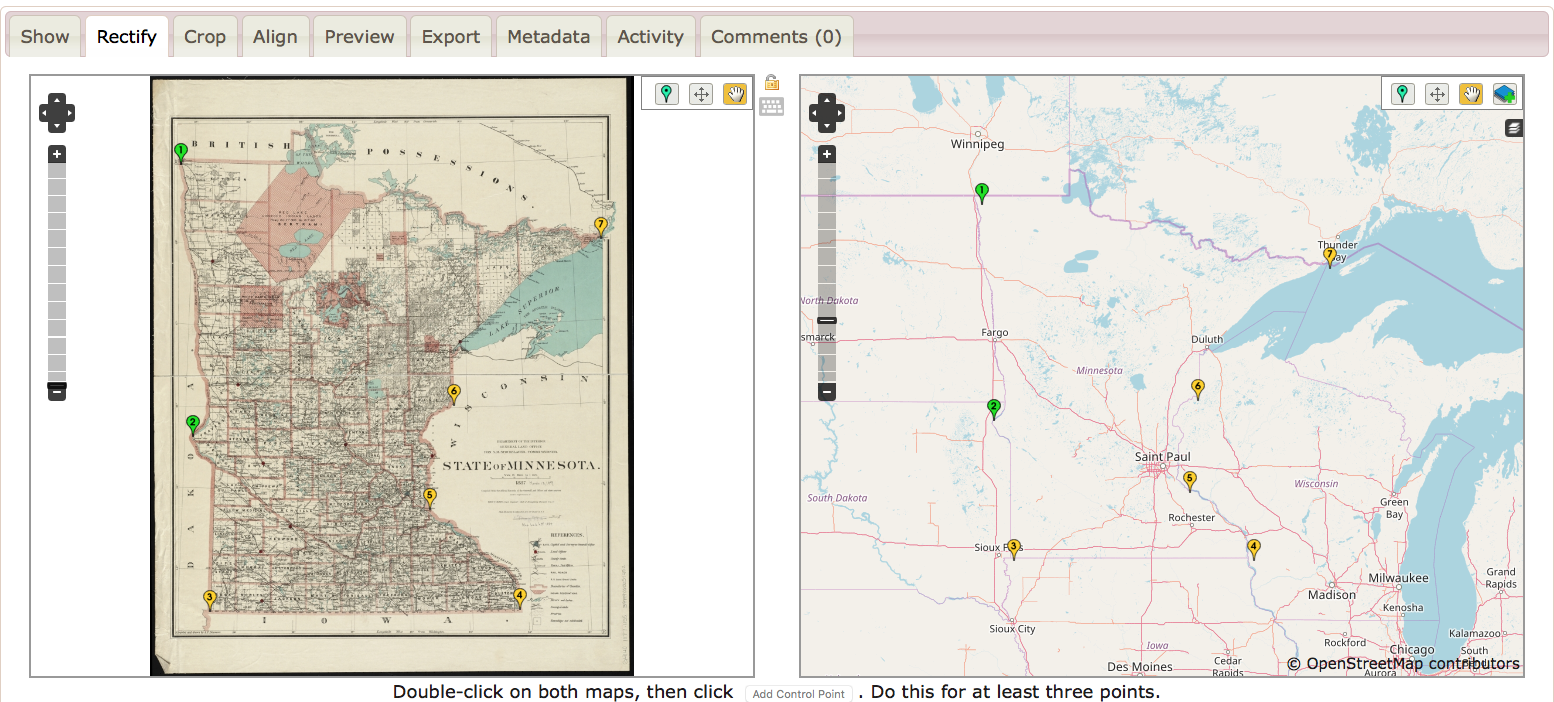

In order to reconstruct past landscapes like the Gettysburg battlefield, the first step is often digitizing the data recorded in a historic map by georeferencing (or georectifying) that image — that is, aligning the historical map or image with its location on the earth in a known coordinate system. There are many ways to do this, but we will start with a cloud based solution requiring no complex software.

The David Rumsey Map Collection is a vast archive of scanned historic maps, mostly covering North and South America. They have enabled a crowd sourcing technique to get the public to help georeference these images for use in GIS applications. The previous version was very buggy and not very accurate, but they have made improvements recently in version 4.

Georecity a historic map:

- Go to the David Rumsey Georeferencer page

- Use the “Search Luna for a map to georeference” button to find a map to reference.

- Find a historic map of a city in Minnesota before 1900 and click View In Georeferencer

- OR

- Add a new map by

- Going to Boston Public Library’s Norman B. Leventhal Map Center and find a historic map of a city in Minnesota before 1900

- Download the map in the original tiff resolution

- Upload the map at https://www.georeferencer.com/maps/new

- Use their tool to set control points (at least 5 are recommended), clip the map area, and rectify the map

- When you are finished, you will see the map overlaid on a basemap of the world.

- Use the “Search Luna for a map to georeference” button to find a map to reference.

Assignment

When you are finished, get the sharing link and post your thoughts on the process along with the link to your work in a COMMENT ON THIS POST.

Resources

Lincoln Mullen of the Center for New Media and History at George Mason University has developed a fantastic resource for getting started with mapping for the humanities.

The Spatial Humanties Workshop site he developed will give you a detailed introduction to the different types of maps you might want to make as a digital humanist, the software and libraries that are out there to use, and most importantly the academic issues and theoretical questions that are raised by mapping humanities data in a digital space.

NB: Another great tool for online rectifying is MapWarper.

- For an alternate, follow these instructions from Lincoln Mullen to Georectify a map with MapWarper

- Use their tool to set control points (at least 5 are recommended), clip the map area, and rectify the map

- When you are finished, you will see the map overlaid on a basemap of the world.

I found a map of Minneapolis from 1981 using the Luna search. This map was partially overlaid on the city of Minneapolis, but it wasn’t exact. So, I went about adjusting the error. I found landmarks that were similar over time: railroad lines, street intersections, and bodies of water. I’m sure some of these landmarks have shifted over time, and the original map seemed hand drawn. Then, since the old map had extra data on it such as a scale and old landmarks, I cut it down to only display the physical map. By the end, I had the old map of Minneapolis overlaid on the new city as close as I could get it.

Here is my final product: https://davidrumsey.georeferencer.com/compare#696783956032

I found this process to be very fun, trying to layer two representations of the same place against one another. To find the specific points that occurred in both times of whatever area the map represents was satisfying, especially when the final product showed the connection so clearly. Once the control points were set, the tools that they allowed the user to work with showed the seamlessness of the overlaid maps (if the selected points were correct). The first time I tried, I selected two points that were at the wrong locations which meant that the overlaid maps weren’t coherent, warping the overlaid map at this spot. After a few more tries, the points I picked worked perfectly and the result, especially when looked at with the opacity tool, was fun to mess around with. It is amazing that more than 100 years after this map was created, the same city blocks, same river bend and even similar bridge locations can be found.

https://davidrumsey.georeferencer.com/maps/666724522059/view#451017809054

The process of finding a map wasn’t too hard. I found the map of minnesota itself. The links are:

https://maps.georeferencer.com/georeferences/534968737983/2018-01-22T20:37:09.271005Z/wmts?key=smplSKXiaUbAf8gVB6R4&SERVICE=WMTS&REQUEST=GetCapabilities

https://maps.georeferencer.com/georeferences/534968737983/2018-01-22T20:37:09.271005Z/map.json?key=smplSKXiaUbAf8gVB6R4

The process of referencing places on the map to ones on Google Maps was pretty easy. It was a very painless process, with the only annoyance being the fact that the website was slightly unintuitive. Other than that, it was pretty fun!

I found a map of St Paul published in 1891 to georeference in this project. I found it was difficult at first to match the locations between this map and the reference. However, I learned that it would be easier to just match borders rather than specific cities or lakes. I also found the tool overlay to be easier to use; I just drag a specific point on the map to its matching location on the reference. I decided not to use the coordinates tool, since it would have required a precise tagging in such a small city. I think this map is now quite accurately overlaid on the reference; I was surprised by how accurate the mapping of St. Paul in 1891 and how little the city has changed.

Here is my final result:

https://davidrumsey.georeferencer.com/maps/777907070021/view

I really enjoyed exploring through these projects. After working on geofencing my out map the precision of the other digital humanities projects really came to light. I initially tried to overlay a map of California over the map, but it was to big. I settled on a map of the bay area and surrounding places. At a first glance they seemed so similar, but getting down to the nitty gritty show the stanch differences between the maps. When zooming in the little differences came out, but overall it turned out fine. https://www.georeferencer.com/compare#942550103010

I found a new map of Minneapolis from 1921 and georeferenced that. I was surprised by how easy it was to put the two places together, and how accurate the old map seemed. I also found the whole process, interface, and tools available very easy to use. In addition, the process of matching old to new let me see a little bit about what has changed in Minneapolis; a graveyard doubled in size, highways were built through the city, more roads were built over the river. But a lot has stayed the same, too; most street names are the same, and the same streets that were centers of activity in 1921 seem to remain active and bustling today.

Overall, this project seemed one of the better ones I explored today. It was easy to use and intuitive, both in actual operation of the interface and, more importantly, how easy it was see patterns or draw conclusions. The Gettysburg project was easy to use in similar ways. The Roman Empire project had an easy to use interface, but there was so much information presented without much explanation it was hard to draw conclusions. The NYPL project was both hard to use and interpret. However, by looking at the well-executed projects, I came to definitely understand how mapmakers can make an argument with maps and which information they choose to include with them.

https://www.georeferencer.com/maps/47648044329/view

I really enjoyed the detail work of correcting and orienting the map. I found a map of the city of Mankato from 1874 that already had a couple control points on it. This meant that the overlay within a few parts of the map was pretty close, and it was cool to switch between the old map and the new and see how the streets and spaces between them in the core of the city remain almost unchanged, even after almost 150 years. I found that using the river made my work a lot easier. I was able to find a bridge that was only slightly off from where a bridge stands today and correct it. I found that lining up the river on the old map with the river on the new helped with the detail-work a lot. I also enjoyed clipping the map to get rid of the surrounding “book” that was scanned in, especially because the map I found had some areas sticking out of the borders.

I definitely enjoyed this exercise. It felt like I was actually contributing something to a project, and I had a a fun time with the visual aspect of of changing the map so that it was more accurate.

https://davidrumsey.georeferencer.com/maps/305880559341/georeference

Georeferencing a map is pretty easy for me. It was particularly interesting to see where lakes have disappeared in the Twin Cities today and where additional land is made compared to when the map came into existence. I’ve learned how inaccurate some maps are when it comes to the actual shape of a land or lake, but I still manage to get the congruity of the maps right.

https://davidrumsey.georeferencer.com/maps/131627739922/georeference

I overlayed a map of Hennepin County from 1874. This was a fun exercise because I know this area well and it was interesting seeing cities that have formed since 1874 and how the boundaries of existing cities have changed slightly. The lack of details in the old map made it difficult to be precise when overlaying, but i managed to use rivers, lakes, and the boundaries of the map to match it with the modern day map.

https://davidrumsey.georeferencer.com/compare#map/508769316375

I found a map of Minnesota in 1874. This was a fun and fairly easy exercise. t was pretty interesting to compare the cities and the geography of Minnesota over a century ago to Minnesota now. The map of Minnesota in 1874 mostly showed distances around railroads and towns the railroads cross.

https://www.georeferencer.com/maps/314684792268/view

I chose to use a map of Minneapolis from 1891 for this assignment. The map from 1891 was already pretty well overlaid the current map of Minneapolis but needed a little bit of tinkering. I found it easy to match up bodies of water like lakes, and the Mississippi River in order to find the best fit. I had a fun time using the georeferencing tools to see how badly I could distort the overlay and then put it back in its correct position.

https://davidrumsey.georeferencer.com/maps/666724522059/view

I had trouble with this website I do not know why but I could not put points down for the life of me and either it was just me not understanding how to do it properly or my computer was just not cooperating with me. I was able to put one point down but I couldn’t put anymore down for some reason and I found my map and such but it was just being weird with me and not letting me overlay it at all because I needed points which I couldn’t put down for some odd reason!

I chose to do a map of Minnesota from 1891. The assignment was fairly simple. I didn’t really experience any problems when it came to overlaying the map. My map displayed the the lands of Minnesota along with the the lands that the Dakota tribe used to inhabit. I found the exercise fairly useful though.

https://davidrumsey.georeferencer.com/maps/144934916872/view